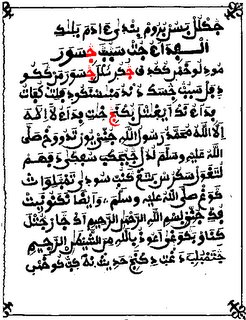

وأما الثانية فيعسر ضبطها جدا لأن الفاظها كلها عجمية ومع ذلك فتلك الالفاظ قد اندرست اليوم وعدم من يعرفها لأن اللغات تتبدّل فكل سنة تنسى كلمات ويوتى بآخر غير معهودة ولولا محافظة الناس على اللغة العربية في الدهر الذي نزل فيه الوحي تبدلت بالكلية حتى لا يوجد من يعرفها ويدلّ على ذلك ان العرب الاقاح في هذا الدهر الذي نحن فيه قد تغيرت السنتهم حتى لا يتكادون يفهمون العربية الاصلية الا ان يتعلموها وتسمى هذه الثانية بالمزروف ومطلعها:

اترگ نئك اراكلئذ * ايشذ ننتا شد اذچان

ايش اتؤچش اذ تنجگفئذ يسگذان اشرن يستغان

قوله اكلئد اي السلطان

وقوله اتؤجش اي وجوده

وقوله تنجگفئذ اي القدم

وقوله نِ اي انا اي القائم بنفسه

"As for the second [poem], it is very difficult to determine it, because its words are all non-Arabic, yet those words have become rare today and no one knows them any more – since languages change. Every year some words are forgotten, and others, little-known, are brought forth. If people had not preserved the Arabic language at the time when the revelation came down, it would have changed completely, to the point that no one would know it. This is shown by the fact that the tongues of the Arabs of our time have changed, until they can barely understand original Arabic unless they have studied it. This second [poem] is called "al-Mazrūfa", and it opens with:

əttäräg niʔk är ägälliʔḏ – äyš äḏ nəttä šd äḏžān

äyš ätuʔž-əš äḏ tənd'əgfiʔḏ – yässəgḏān āš ni yəstəġān

("I ask of the Sultan * He who is my owner

Whose existence is eternity without beginning * who is rich, who needs nothing")

- His saying ägälliʔḏ means "Sultan".

- His saying ätuʔž-əš means "his existence".

- His saying tənd'ägfiʔḏ means "eternity without beginning".

- His saying ni means "I" ie "the independent"."

From Taine-Cheikh (2007), we find that ättər is "ask", and əttär-äg therefore perfective "I ask"; niʔk is "I" (note the carefully written glottal stop!); and är is "from". Perhaps unsurprisingly given this passage, ägälliʔḏ has not made it into the modern era, so the vocalisation is conjectural, but it is obviously cognate with Tashelhiyt agllid "Sultan". äyš is a relative complementiser ("that") normally combined with a resumptive pronoun; äḏ is the copula ("is"); nəttä "he" is presumably the expected resumptive pronoun (the text actually clearly has two n's, but I'm assuming one of them is a typo). The rest of the line is a bit of a mystery; my best guess is that it involves the perfective participle of the verb "own", äyi(ʔ) in Taine-Cheikh (note that her y is often ž in other Zenaga varieties, from original *l), but then I would expect a glottal stop to be written. äyš "that" we have already seen, and -əš is "his/her/its". ätuʔž, explained as "existence", must be derived from the verb y-uʔy "exist", but the t is surprising. äḏ "is" we have already seen. We are given the meaning of tənd'ägfiʔḏ, but even its vocalisation is conjectural, and I can't find an appropriate root to relate it to. yässəgḏān (vocalisation conjectural again) must be a participle of the verb corresponding to Ould Hamidoun's eʔssəgḏīh "richesse", quoted by Taine-Cheikh (note that vowel length, phonemic in Zenaga, is transcribed accurately!). The rest is another blur, except that yəstəġān (?) may be from Arabic istaġnā "not to need".

If this isn't enough of a challenge, there's several other lines of Zenaga poetry quoted in that article...