Given the popularity of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in population genetics, it's worth a historical linguist's while to have some idea of how it works and how it's applied there. This popularity might also suggest at first glance that the method has potential for historical linguistics; that possibility may be worth exploring, but it seems more promising as a tool for investigating synchronic language similarity.

Before we can do PCA, of course, we need a data set. Usually, though not always, population geneticists use SNPs - single nucleotide polymorphisms. The genome can be understood as a long "text" in a four-letter "alphabet"; a SNP is a position in that text where the letter used varies between copies of the text (ie between individuals). For each of m individuals, then, you check the value of each of a large number n of selected SNPs. That gives you an m by n data matrix of "letters". You then need to turn this from letters into numbers you can work with. As far as I understand, the way they do that (rather wasteful, but geneticists have such huge datasets they hardly care) is to pick a standard value for each SNP, and replace each letter with 1 if it's identical to that value, and 0 if it isn't. For technical convenience, they sometimes then "normalize" this: for each cell, subtract the mean value of its (SNP) row (so that the row mean ends up as 0), then rescale so that each column has the same variance.

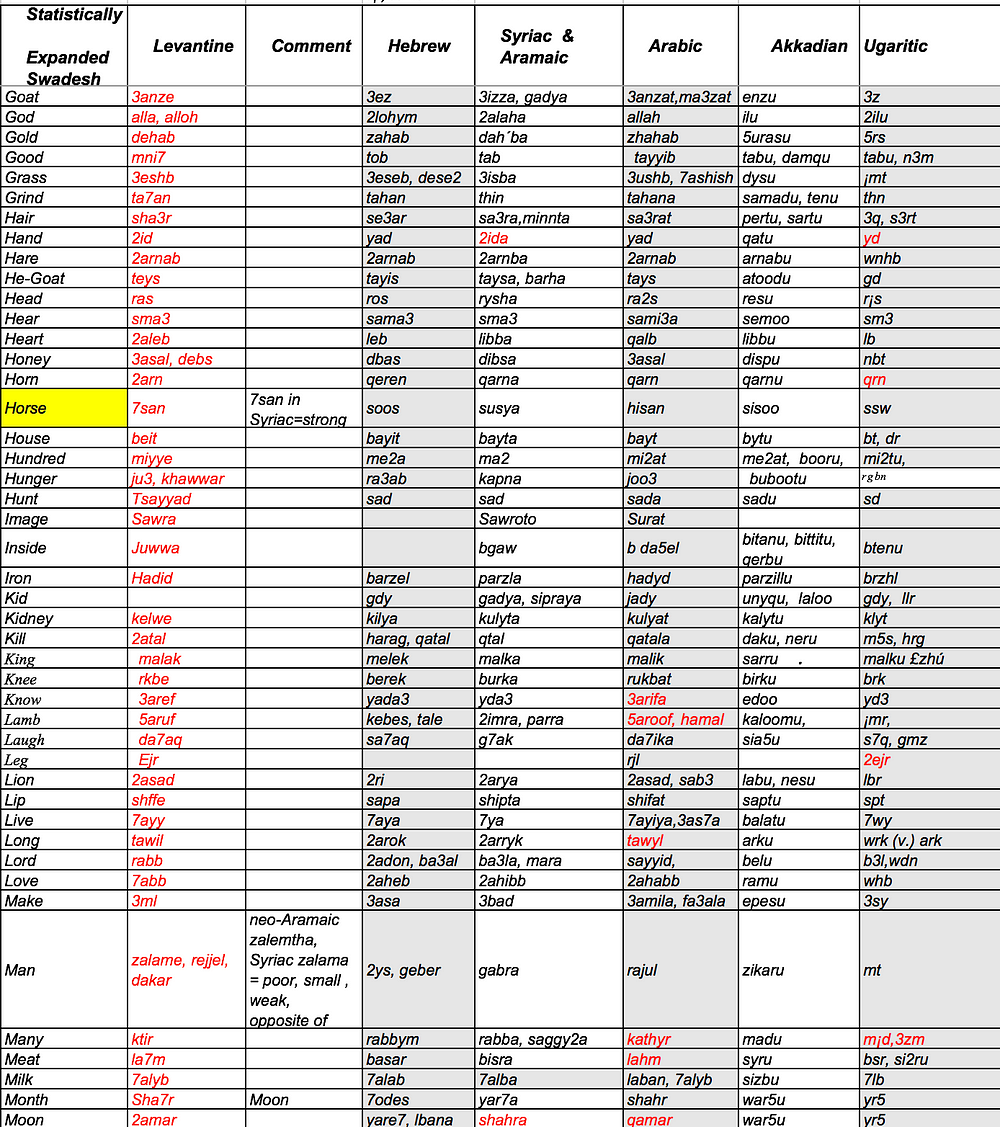

Using this data matrix, you then create a covariance matrix by multiplying the data matrix by its own transposition, divided by the number of markers: in the resulting table, each cell gives a measure of the relationship between a pair of individuals. Assuming simple 0/1 values as described above, each cell will in fact give the proportion of SNPs for which the two individuals both have the same value as the chosen standard. Within linguistics, lexicostatistics offers fairly comparable tables; there, the equivalent of SNPs is lexical items on the Swadesh list, but rather than "same value as the standard", the criterion is "cognate to each other" (or, in less reputable cases, "vaguely similar-looking").

Now, there is typically a lot of redundancy in the data and hence in the relatedness matrix too: in either case, the value of a given cell is fairly predictable from the value of other cells. (If individuals X and Y are very similar, and X is very similar to Z, then Y will also be very similar to Z.) PCA is a tool for identifying these redundancies by finding the covariance matrix's eigenvectors: effectively, rotating the axes in such a way as to get the data points as close to the axes as possible. Each individual is a data point in a space with as many dimensions as there are SNP measurements; for us 3D creatures, that's very hard to visualise graphically! But by picking just the two or three eigenvectors with the highest eigenvalues - ie, the axes contributing most to the data - you can graphically represent the most important parts of what's going on in just a 2D or 3D plot. If two individuals cluster together in such a plot, then they share a lot of their genome - which, in human genetics, is in itself a reliable indicator of common ancestry, since mammals don't really do horizontal gene transfer. (In linguistics, the situation is rather different: sharing a lot of vocabulary is no guarantee of common ancestry unless that vocabulary is particularly basic.) You then try to interpret that fact in terms of concepts such as geographical isolation, founder events, migration, and admixture - the latter two corresponding very roughly to language contact.

The most striking thing about all this, for me as a linguist, is how much data is getting thrown away at every stage of the process. That makes sense for geneticists, given that the dataset is so much bigger and simpler than what human language offers comparativists: one massive multi-gigabyte cognate per individual, made up of a four-letter universal alphabet! Historical linguists are stuck with a basic lexicon rarely exceeding a few thousand words, none of which need be cognate across a given language pair, and an "alphabet" (read: phonology) differing drastically from language to language - alongside other clues, such as morphology, that don't have any immediately obvious genetic counterpart but again have a comparatively small information content.

Nevertheless, there is one obvious readily available class of linguistic datasets to which one could be tempted to apply PCA, or just eigenvector extraction: lexicostatistical tables. For Semitic, someone with more free time than I have could readily construct one from Militarev 2015, or extract one from the supplemental PDFs (why PDFs?) in Kitchen et al. 2009. Failing that, however, a ready-made lexicostatistical similarity matrix is available for nine Arabic dialects, in Schulte & Seckinger 1985, p. 23/62. Its eigenvectors can easily be found using R; basically, the overwhelmingly dominant PC1 (eigenvalue 8.11) measures latitude longitude, while PC2 (eigenvalue 0.19) sharply separates the sedentary Maghreb from the rest. This tells us two interesting things: within this dataset, Arabic looks overwhelmingly like a classic dialect continuum, with no sharp boundaries; and insofar as it divides up discontinuously at all, it's the sedentary Maghreb varieties that stand out as having taken their own course. The latter point shows up clearly on the graphs: plotting PC2 against PC1, or even PC3, we see a highly divergent Maghreb (and to a lesser extent Yemen) vs. a relatively homogeneous Mashriq. (One might imagine that this reflects a Berber substratum, but that is unlikely here; few if any Berber loans make it onto the 100-word Swadesh list.) All of this corresponds rather well to synchronic criteria of mutual comprehensibility, although a Swadesh list is only a very indirect measure of that. But it doesn't tell us much about historical events, beyond the null hypothesis of continuous contact in rough proportion to distance; about all you need to explain this particular dataset is a map.

(NEW: and with PC3:)