But I don't have all day to spend beating this dead horse, and doing etymology properly takes time. So let's just have a quick look at the first page of his wordlist (well, probably the second one - the real first one seems to be missing), and leave the other pages as an exercise for the reader.

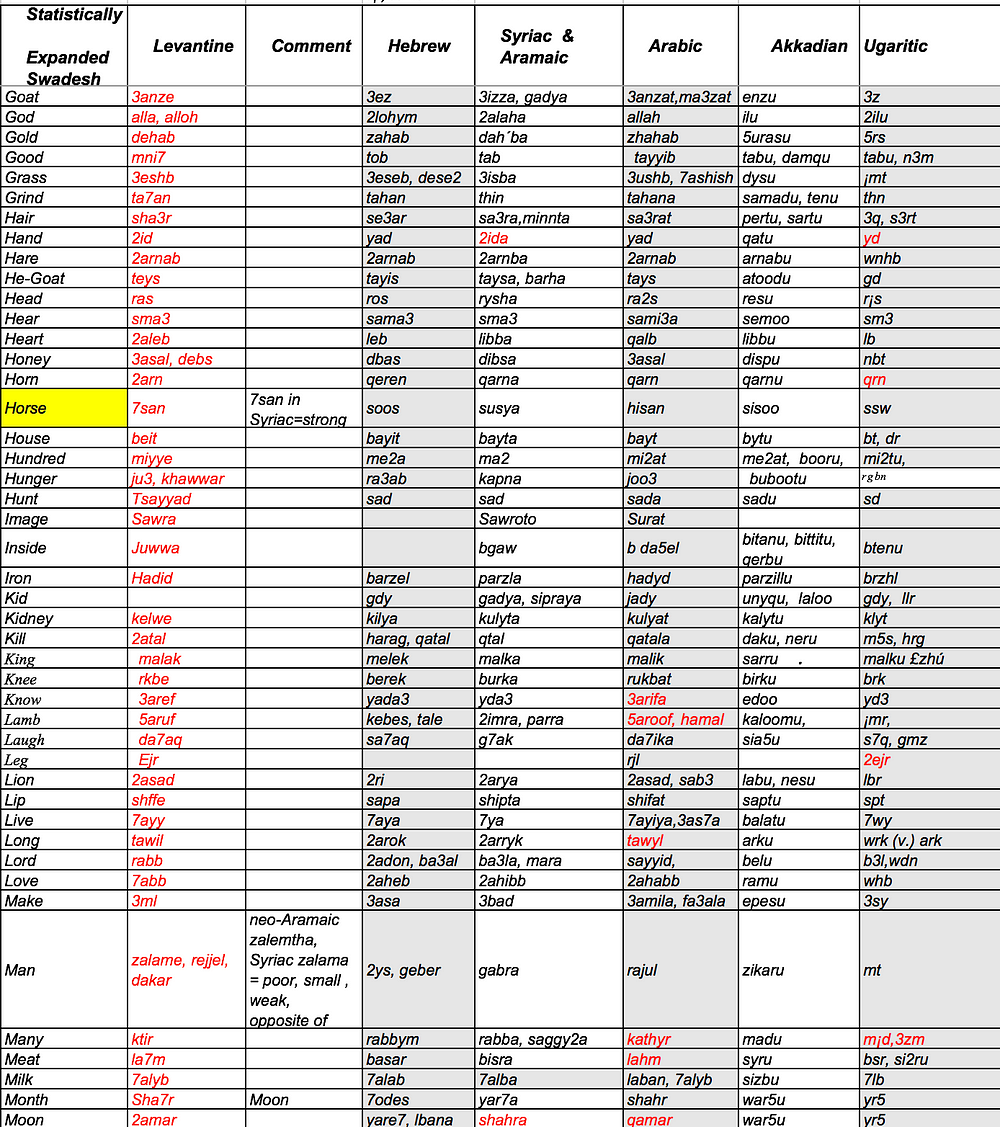

Out of these 39 words, 18 seem to be unambiguously Arabic in origin - either they share specific sound changes with Arabic to the exclusion of the rest of Semitic, or they use a root not used in the appropriate meaning elsewhere in Semitic. Only two look like being Aramaic rather than Arabic in origin (and the evidence in both cases is fairly weak): "hand" and the patently non-basic vocabulary word "image". (Taleb would add a third, zalame "man", but this word has an at least equally plausible Arabic etymology, making it ambiguous at best.) The remaining 19 words are ambiguous, and could in principle derive from any of more than one Semitic languages - but even there, the situation is not symmetrical; all 19 could derive from Arabic, whereas no more than 11 of them could derive from Aramaic. The unambiguous cases give the following ratio: 18 Arabic : 2 Aramaic : 0 everything else. On that basis, we should therefore expect 90% of the ones ambiguous between Arabic and Aramaic (ie all but one) to derive from Arabic, not from Aramaic, and all of the ones ambiguous between Arabic and another Semitic language but not Aramaic to derive from Arabic. For details, see the following table:

| 1 | goat | Arabic | does not share Canaanite+Aramaic+Ugaritic *nC > CC; does not share Akkadian *ʕa > e |

| 2 | god | Arabic / Aramaic | shows innovative gemination of the l, attested only in Arabic and some dialects of Syriac |

| 3 | good | innovative | the Arabic etymology is obvious, but the root is pan-Semitic so we may generously assume that it could in principle have derived from some other branch |

| 4 | grass | Arabic | does not share Aramaic and Phoenician *ś > s ; does share Arabic *ś > š |

| 5 | grind | Arabic / Canaanite | does not share Akkadian *aħa > ê ; does not share Aramaic CaCVC > CCVC |

| 6 | hair | Arabic / Ugaritic | does not share Aramaic and Phoenician *ś > s ; does share Arabic *ś > š ; does not share Akkadian loss of *ʕ |

| 7 | hand | Aramaic | although a change of *yad > *īd is natural enough that it could easily have happened independently in Arabic... |

| 8 | hare | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Akkadian | no distinctive innovations |

| 9 | he-goat | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic | no distinctive innovations |

| 10 | head | Arabic / Ugaritic | does not share Canaanite *aʔ > *ā > ō nor Aramaic *aʔ > ī nor Akkadian *aʔ > ē ; the form rās (with loss of the glottal stop) is well-attested in early Arabic dialects |

| 11 | hear | Arabic | does not share Aramaic and Phoenician *s > š (I'm going with Huehnergard's reconstruction of proto-Semitic sibilants here). Note that the correct Syriac form is šmaʕ, not sma3 ; likewise the Hebrew |

| 12 | heart | Arabic | The initial glottal stop (still pronounced q in, for example, Alawite dialects) can only be explained from the Arabic form, which is a lexical innovation replacing original *libb |

| 13 | honey | Arabic | 3asal is clearly Arabic, and – as I've pointed out before – dabs is attested in Classical Arabic as well as in Hebrew and Aramaic |

| 14 | horn | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Akkadian / Ugaritic | no distinctive innovations |

| 15 | horse | Arabic | Syriac ḥsan 'strong' has s, not ṣ, but even if it were cognate, the Classical Arabic and Levantine form still share a semantic shift unattested in Aramaic |

| 16 | house | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Ugaritic | Akkadian can be ruled out, since it shows a shift *ay > ī which never happened in Levantine. |

| 17 | hundred | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Akkadian / Ugaritic | The only innovation here, ʔ > y, is not shared with any of the ancient language in question |

| 18 | hunger | Arabic | Even assuming jūʕ has cognates elsewhere in Semitic, the change g > j is specific to Arabic |

| 19 | hunt | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Akkadian / Ugaritic | The only innovation here, use of the D-stem, is not shared with any of the ancient languages |

| 20 | image | Aramaic | Since when is 'image' basic vocabulary? But yes, assuming we can trust the transcription, it shares the aw with Aramaic |

| 21 | inside | Arabic / Aramaic | Mixed signal here: the meaning looks like Aramaic, but the sound shift g > j is Arabic not Aramaic. In reality, the word *jaww must originally have meant 'inside' in Arabic too; it lost this meaning in Classical Arabic, but kept it in many of the dialects |

| 22 | iron | Arabic | |

| 23 | kidney | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Akkadian / Ugaritic | The only innovation here, *y > w, is not shared with any of the ancient languages (but _is_ shared with many other modern Arabic dialects...) |

| 24 | kill | Arabic / Canaanite | Does not share Aramaic CaCVC > CCVC |

| 25 | king | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic / Ugaritic | Since when is 'king' basic vocabulary? |

| 26 | knee | Arabic | Shares a unique innovation with Arabic – the metathesis brk > rkb |

| 27 | know | Arabic | |

| 28 | laugh | Arabic | Shares a unique innovation with Arabic – the sound shift *ɬ' > ḍ (which came relatively late in Arabic – later than Sibawayh, even – and never happened in any other Semitic language). I can't speak for Amioun, but in general Levantine has ḍaḥak; if Amioun does have ḍaḥaq, the fact that it didn't become *ḍaḥaʔ suggests that the *k > q happened there only after the regular shift *q > ʔ, and hence has nothing to do with the Canaanite or Ugaritic forms. |

| 29 | leg | innovative | The alleged Ugaritic form is nonsense – Ugaritic had no j sound, and the dictionary of Del Olmo Lete and Sanmartin reveals no appropriate Ugaritic form. It is true that the Levantine form seems to be shared with Ethiopic and some Yemeni dialects, but not with any ancient language of the Fertile Crescent. |

| 30 | lion | Arabic | A very problematic choice as 'basic vocabulary'. |

| 31 | live | Arabic / Canaanite / Aramaic | Except that the Levantine form is clearly 'alive', not 'live', making the whole comparison problematic.... |

| 32 | love | Arabic | The Arabic is of course mistranscribed - in his terms, it should be 2a7abba, whereas the Hebrew and Aramaic forms really do have a h. |

| 33 | make | Arabic | |

| 34 | man | innovative | 'zalame' is etymologically problematic – both Arabic and Aramaic etymologies have been proposed. 'rejjel' is of course from Arabic. dakar is 'male', not 'man'. |

| 35 | many | Arabic | |

| 36 | meat | Arabic | This shares a specific semantic shift with Arabic to the exclusion of the rest of Semitic : « staple food » > « meat » |

| 37 | milk | Arabic / Ugaritic | The root is common to several Semitic languages, but the use of the passive pattern fa3īl in this word is unique to Arabic |

| 38 | month | Arabic | Pretty sure the normal Levantine form is shahr, not sha7r, not that it makes any difference to the etymology – and for sure Syriac 'moon' below is sahrā, not šahrā. |

| 39 | moon | Arabic |

9 comments:

The only one of these where I might quibble with you here is 'juwwa'. The Arabic jaww itself is probably an early Aramaic borrowing and I suspect that even its use in Q16:79 retains the original meaning of "inside".

That said, in many, many Persian loanwords, some of which would've almost certainly been post-conquest borrowings (I realize how hard this is to establish, but there's a whole host of Persian borrowings like this in Abbasid poetry that only make sense in a post-conquest cultural context) g is borrowed as j or appears with alternate forms as either j or q. So, I'm not sure that g > j can in itself determine that a word is not a post-conquest loanword.

If it was a borrowing, then its Qur'anic use suggests that it was a pre-conquest one. I wouldn't exclude that possibility. But I suspect it of being a common inheritance rather than a borrowing from Aramaic into Arabic; "dāxil" is a very transparent formation. A dialect map of "inside" would be useful here, but I don't think that volume of Behnstedt & Woidich is out yet.

Note that gw' (guwwa) 'inside' and br' (barra) 'outside' are also a pair in Aramaic, as they are in Arabic. If they are loans, then it is very possible that they diffused to Arabic from Nabataean or Palmyrene Aramaic. The final /a/ vowel could be a reflex of the accusative in Arabic, or the terminative (which forms adverbs as well) < *ah < *Vs in Aramaic. As for the g = j pairs, it seems that the earliest stratum of Levantine Arabic had a [g] realization of Jim (Proto-Semitic *g), as early loans into Neo-Aramaic have a velar reflex of Arabic jim. Thus, early Aramaic loans into Arabic would have undergone the g > j change, along with native vocab. Brilliant piece as usual, Lameen! Thank you!

Taleb aside, is there any evidence for any early non-Aramaic Semitic words in the Lebanese or Coastal Syrian varieties of Arabic?

Ahmad: Thanks for the helpful comment!

Whygh: Can't think of any reliable references offhand for Lebanon, but a couple have survived in Palestinian Arabic, as shown for instance by Mila Neishtadt: The Lexical Component in the Aramaic Substrate of Palestinian Arabic (notwithstanding the title, she gives one or two words that predate Aramaic.)

Also relevant in this connection, though less thorough: Hebrew and Aramaic Substrata in Spoken Palestinian Arabic, by Ibrahim Bassal.

You have quite literally said yourself here that only 18 of the words on the list "seem" to be "unambiguously" Arabic. Going with your own ratios, that is only a 46% solid assertion of words that are "indisputably" of Arabic origin. Does that sound overwhelmingly Arab to you? Because to me (and going by preschool-level mathematics) that sounds like a little less than half (50%). Lebanese is a central Semitic dialect, meaning that it is influenced by many Northwest Semitic languages. Originally, Arabic is a South Semitic language, so Lebanese dialect lies right in the middle of these categories. Unless you're a Lebanese/Levantine Arab, I fail to understand your people's obsession with Lebanese/Levantine Christians, who are by all historically veracious accounts the indigenous peoples of the Middle East. Taleb aside, the obsession of general, random Arabs in claiming these minority communities and their cultures as their own is extremely cringey, especially when taking into account the continued history of ethnic, religious and sectarian persecution. This is especially strange when taking into account that if not Lebanese being a "high" proliferated dialect in TV and media, you would likely struggle to understand them (unless you speak some other Levantine dialect). Lebanese has been shown to have an Aramaic substratum, so by your own admission and statistics, this is not the flex you think it is. Infact, the thesis is as poorly thought out as Talebs. Seeing this never-ending debate being fueled solely by bias is once again extremely cringe-inducing. It would be preferable to allow non-biased linguists, who know little of the centuries-long contentious politics of the Levant, to do a deep analysis of the links of this dialect to its predecessor languages and influences.

Think as clearly as you can about what "ambiguous" means in the context of deciding whether Arabic is the principal source of Lebanese vocabulary or not, and try again. (Hint: if you're trying to argue that French is descended from Sanskrit not Latin, you don't waste your readers' time with words like "mother" that are practically the same in Sanskrit and Latin; only words that are different can help or hurt your case.) South Semitic is an obsolete hypothesis, by the way, and the Aramaic substratum of Lebanese - like most substrata in most languages - accounts for only a tiny portion of its vocabulary and grammar.

As for the rest, you seem to have me confused with someone else. If Taleb wants to identify as a Mediterranean or a Phoenician or whatever rather than an Arab, that's his business; it seems kind of cringey to me, but it's his life. If he can convince enough Lebanese that what they speak is a separate language, then it will be: standard languages are socially constructed. Neither of those can change the linguistic facts, though: Lebanese still descends from Arabic, no matter who the Lebanese descend from or identify with, and no matter whether they speak a "dialect" or a "language".

I am not necessarily arguing here that Lebanese speak a "different" language, I think it is reasonable to call Lebanese dialect: Arabic, Lebanese Arabic, or Lebanese as it is quite literally all of these at once, it's not a huge deal. What I take issue with is the methodology of this article particularly, the other three you wrote were quite good and convincing. The absence of evidence does not equal the evidence of absence, and when speaking about Semitic words one needs to be very careful about extrapolating where "ambiguous" words "may" come from because Northwest Semitic languages are dangerously understudied (since we know many of these groups didn't leave behind stone inscriptions). This is my point of contention, the idea that the ambiguous terms need not be subject to further meaningful analysis. Relegating these interesting terms to "likely Arabic" is too hasty and too political for my liking, (even if they very well may be in the end); it starts to err into Talebian (emotional and reckless) thinking. I think the linguistics of the ancient Northwest Semitic languages is a topic that deserves far more steam & historical weight towards it. Otherwise, I am inclined to agree with you that identification is a combination of many aspects and it is (mostly) held up by being self-constructed, so it need not matter in that sense as Lebanese Arabic is a dialect of Arabic. After all, Maltese is highly mutually intelligible (depending on thickness of accent) to many Levantine and North African dialectical speakers, when understanding Italian or another Latin or romance language, the level of comprehension of Maltese can rise to a comfortable 90%. The labels here are largely political, what matters more is where the languages directly descended from and how they evolved. The Semitic family is a broad one, not all Aramaic dialects are mutually intelligible and not all Arabic dialects are mutually intelligible. I think the arguments made in the other 3 articles that dispel the structure of Taleb's arguments are highly cogent so well done on that front.

Post a Comment